| |

|

FAMILY HERITAGE

One aim of the Qurna History Project is to collect photos of identifiable

Qurnawi and where possible ‘return ’these family photos.

Visitors have been taking photos here for 150 years and the images

are in public and private collections and bottom drawers, all over

the world. We are collecting copies of such photos - taken any time

from the 1850s to 20 years ago - and taking copies back to give

to the family.

The back of this photo says “Femmes indigenes, Cheikh el-Gournah

(Tombeaux des nobles), Fevrier 1959 ”.

The older

of these two lovely women is Bahia Ali Mohammed,her daughter is

said to be Sikkina. Sikkina now lives in Armant, but a nice A4 copy

is with her family waiting for the next visit.

|

|

|

Thank you to Victor

Blunden and Anne Midgley for sending copies of your families ’

photos.. The young children with the baby goat snapped in 1982?

The little girl has a family of her own in As-Siyul.

|

Three children, two

naked,near the Colossi in 1931 have proved difficult to trace,perhaps

partly because of the nakedness. But they provoked discussion

as to whether the naked boys were poor or sick. Until quite recently

many village children did not wear clothes, but as at least one

of these children seems to have the distended belly typical of

malnourished children, perhaps poor and sick is the answer.

|

|

|

The photo of the Davamalli

saqieh near the Ramesseum pylon is also a portrait of our present

guardian’s grandfather!

|

It is hoped that all

the collected portraits will form an exhibition in their own right

- one day. If your family has any photo records of Egypt visits

before 1980, please do look and see if you have any with recognizable

Qurnawi in the holiday snap. We would be grateful for copies,

together with any relevant information as to date, place etc that

might help in identifying families.

|

SHEIKH

AWAD

c.1773-c.1868

Egyptian guide,foreman and local historian

Jason

Thompson, a historian working at The American University in Cairo,

biographer of Sir Garner Wilkinson and an expert on E. W. Lane put

us on the track of Sheikh Awad. Jason had found a photo of the old

man in his 90s, and then we tracked down a portrait drawn by Nestor

L’Hote in 1828 which is reputed to be the much respected local

historian.

It appears

that nearly every family on Sheikh abd el Qurna is descended from

Sheikh Awad, or is able to trace a very close connection. It was

clear that these photos had to be shared with the family, and as

we also knew a descendant of one of the Sheikh’s neighbours

and friends in the 1820s, this had to be celebrated.

|

|

Sheikh Awad was born

and lived in Qurna all his life. Joseph Bonomi was born in London

and lived in Qurna for nine years, 1824-32. They were very close

neighbours living on Sheikh abd el Qurna,and would have known

one another well.Many of Bonomi ’s ‘ethnographic ’and

topological notes are likely to have come from Awad, who worked

with Champollion, Lepsius and Brugsch as foreman and guide.Bonomi

worked with Hay, Lane, Wilkinson, Burton and Lepsius recording

Egypt and its monuments. Awad married ten or twelve times and

had more than fifty children.

|

|

Bonomi

married twice and had only a few children.

|

|

|

On March 8th 2001 a rather special tea party was held on Sheikh

abd el Qurna. 60 or so known descendants of Sheikh Awad were invited

to meet Yvonne Neville-Rolfe, great grand-daughter of the sculptor,

draughtsman, traveller and early Egyptologist. Two grand-sons

of Awad came, with dozens of other family members of three or

four generations. Lots of sticky cake was eaten and washed down

with cokes provided whole-sale by Hajj

Abd e ’Satar Ahmed Awad, one of Awad ’s grandsons.The

adult guests were each given a ‘certificate ’momento

showing portraits of both men. It was a very jolly afternoon,

and a memorial to the close friendship and professional links

between the Qurna community and the British.Sadly Hajj Adli, an

Awad grandson in his mid nineties, tall, gentle and for many years

a fixture on the mastaba outside the mosque, died in the summer

of 2003.

(for report of event see ASTENE newsletter 15)

|

Hajj Adli, grandson

of Sheikh Awad, being introduced by one of his many young descendants

to the friend of his grandfather at Qurna Discovery, April 2001.

Hajj Adli died recently carrying much knowledge with him.

It became clear after

this happening that it would be good to find other photos of Qurnawi

people which are now in collections abroad, and bring copies back

to the families concerned. It is often difficult locating the families,

but gradually it will get easier as the whole idea gets better known

locally.

|

|

Hasan abu’l Azab – farm labourer.

This postcard photo was printed for tourists to send home as

an example of curious Egyptian ploughing. Yet again the postcard

carries details of local and personal histories. The Theban Hills

are in the background with dwellings and tombs of Qurnet Marei

seen in the hillside on the far left. This farmland is now owned

by the Abd er Rassul family, and the man ploughing was employed

by them. Hasan abu’l Azab is clearly remembered by many

members of the family because he always worked with a cow and

a camel – not a usual practice. This cow itself was also

remembered as having been particularly big and strong and for

living a very long time. To the left of the animals is one of

the four saqiya which once stood near here. The photo was probably

taken c. 1950-55 as abu’l Azab was about 85 years old when

he died in 2002/3. It is probably the only photo of abu’l

Azab apart from perhaps a wedding photo if the newly weds had

had enough money to go to the studio. Some enlarged copies of

this photo will be taken back to Qurna later in 2005 for family

and friends.

|

|

Fendia, Grandmother of Horubat

Just by chance I might have found the earliest photo of an Upper Egyptian rural woman whose name and family are known. While poking about in second-hand bookshops chasing old images that might have information on Qurna I glanced through an unlikely book on Coptic history, The Light of Egypt by Robert de Rustafjaell, 1909. There were lots of close-up plates of Coptic manuscripts which could only be of interest to the very learned, but then there were two photos taken by the author in Qurna in about 1907. One was of Ahmed Abd er Rassul as an old man at the entrance to the tomb where he and his brothers had found their famous collection of royal mummies in the early 1870s, and the next photo was a group portrait of his family.

This wonderful photo shows four generations of the family: Ahmed then an old man (said to be 90), a daughter carrying a baby girl, and Ahmed’s very elderly mother Fendia (said to be 120). His daughter modestly pulls her smart woven shawl to cover half her face, but Fendia sits in the centre of the photo, supporting herself on two strong sticks, face uncovered, looking directly and seriously at the camera. She is wearing earings – probably wedding gold – and shoes! In 1907 few village people would have worn shoes at all, certainly very few women would have had shoes. They are traditional peasant shoes, made from the hard part of a palm frond, but shoes none the less. Fendia appears very conscious of the significance of having her photo taken by a learned foreign friend of her son. She seems to be showing herself to the world as the powerful woman that she is, and distancing herself from the other women of the village with her shoes. She also exposes her neck and part of her upper body. She is a very old woman, her body is no longer of any sexual significance, so long as she is decent she has no need to worry about covering like her grand-daughter. It is an amazing photo of an elderly woman – any woman, but especially one from rural Upper Egypt.

Taken out of context this is intrinsically a fine photo, but this is far more special, this is a woman we know about from written records of travellers and scholars - she was mentioned in Charles Wilbour’s letters, when Ahmed took him home for tea in 1884. Stories still circulate in the family about this formidable character. And the family is now huge. Most of the population of the area of Horubat (Nobles Tombs) is descended from her, and many people in the rest of Qurna, and the new village of AsSiyuul and further afield. In November 2004 I took back some copies of this photo to give to great-grandchildren and great, great-grandchildren that I know. It was one of them that pointed out the significance of the shoes – something that made him both proud and amused. The widow of Sheikh Ali Abd er Rassul, who was one of Fendia’s grandsons, was astounded when I gave her a photo of her father-in-law’s mother when I met her by chance on an ‘arabiyya bi cabooda’ - a small local bus. The significance of such an early photograph of a local woman was not lost on her either, but she was amazed to see it.

Even allowing for some exaggeration as to her age, Fendia was probably around 100 years old at the time of this photo. This is not so unusual here as there are many very long-lived people in Horubat. Most of us don’t have photos of family members who were alive at the time of Napoleon, perhaps even before Mohammed Ali became viceroy of Egypt. Many people in the UK do not have photos of their grand-mothers, many more don’t have photos of their great, or great great grand-mothers. But Horubat now has Fendia’s portrait. Fendia’s name reflects her Turkish descent. Exactly who her Turkish ancestors were is unclear, but the Turkish connection could have been something which distinguished her in this close-knit, Saidi community, and might have led to her confidence in front of the camera.

Most old photographs of rural women anywhere were taken by passing strangers - tourists or professional photographers - to illustrate ‘foreign’ costume, looks or customs. The identities of individual subjects were of no interest and not known. Cameras were not a common personal or family possession, and in many places, including Qurna, they are unusual even today. Occasionally personal photograph collections will include names of family friends in rural areas, but seldom will these families have a history which connects (albeit briefly) with national history, as do the three Abd er Rassul sons of Fendia. There are very many more photos of men than of women generally in photographic collections (except in the ‘glamour’ or soft porn categories). Men were more likely to be working outdoors, and therefore visible to the curious photographer, and men also featured as colleagues, politicians, soldiers, sailors and merchants. There is an even greater proportion of male subjects in photos taken in Muslim countries. Except for posed studio portraits and photos of the rich and famous, women avoided the camera and covered their faces if they could not. Many women in Qurna still avoid cameras, partly from modesty but mainly from fear and mistrust of the power of the camera and of the ‘stolen’ image itself or the use it could be put to.

The villagers of Qurna would have been some of the first rural people to see cameras in the early 1850s, because the temples and tombs were a magnet for the earliest photographers. However, photographers were mostly interested only in those tombs and temples, and if local people featured at all it was only to give scale to the monuments. Some photographers were interested in ‘local life and customs’, and took photos of peasants ploughing, waterwheels, markets and the like. Some Egyptologists took photos of their excavations that show their workers, but generally no names are given, and others took group portraits of the all male mission staff, where yet again the local Egyptians remain nameless. It is very unusual for someone to take a family portrait because this level of interest, mutual trust and friendship was seldom established. Robert de Rustafjaell had known Ahmed Abd er Rassul for many years, and on this visit he was invited home to tea. It would be fascinating to know whether it was Robert or Ahmed or perhaps Fendia who suggested taking a photograph, and whether she herself ever saw a copy of it.

Here we have a unique photo from c.1907 of a known woman with a name and personal history, with associated stories of her strength and character. She lived in a ‘bab el haggar’ – a dwelling in a New Kingdom tomb on the Theban Hills. Fendia’s vast extended family of descendants lives in houses above and around her old house where she was photographed flanked by her son and grand-daughter one hundred years ago.

Caroline Simpson March 2005

|

|

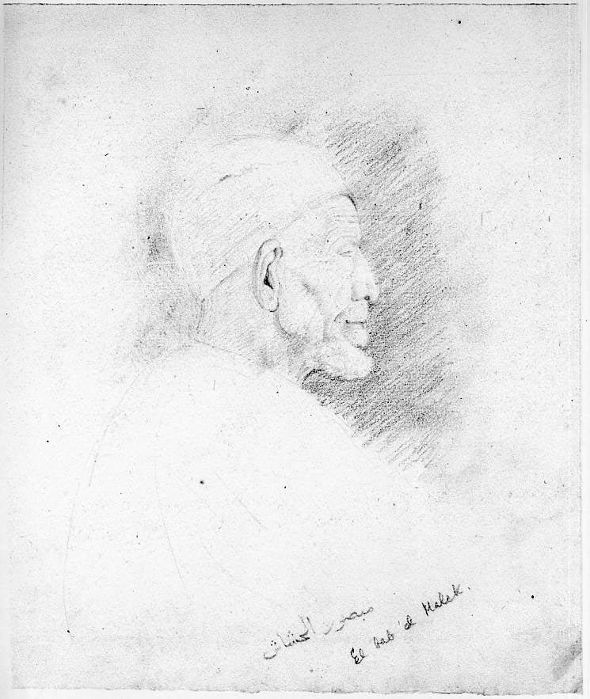

Mansour el-Hashash

Yvonne Neville-Rolfe's family collection includes a fine pencil portrait in profile of an old man with

most distinctive features. Underneath is written in Arabic that this is Mansour el-Hashash, and in

English is written El bab el Malek. The date is unknown but is likely to be c. 1830 when Bonomi

says he was collecting his Topographical Notes for which Mansour el-Hashash appears to have been

one source of his information. Some ten years ago I spent two days in Mrs Neville-Rolfe's cellar

examining a trunk-full of diaries, letters and odd notes. (It was an appropriate subterranean

repository for the personal papers of a man who had spent so long working and living in tombs). A

loose page of this old Bonomi collection says that "Mansour Ashash was born in 1136" - 1723 in

the Gregorian calendar. So we have a portrait of a Qurnawi who was fourteen when two of the

earliest European visitors, Pococke and Norden, visited Thebes - perhaps he saw them...

Read the full story here (PDF). |

Do

please help.

Search the attic and talk to your parents and grandparents, look in

your local library, keep an eye open at second hand sales. Qurna History

Project does not need any original copies – just good scans

or photographed copies, and then we can take them back home.

|

|